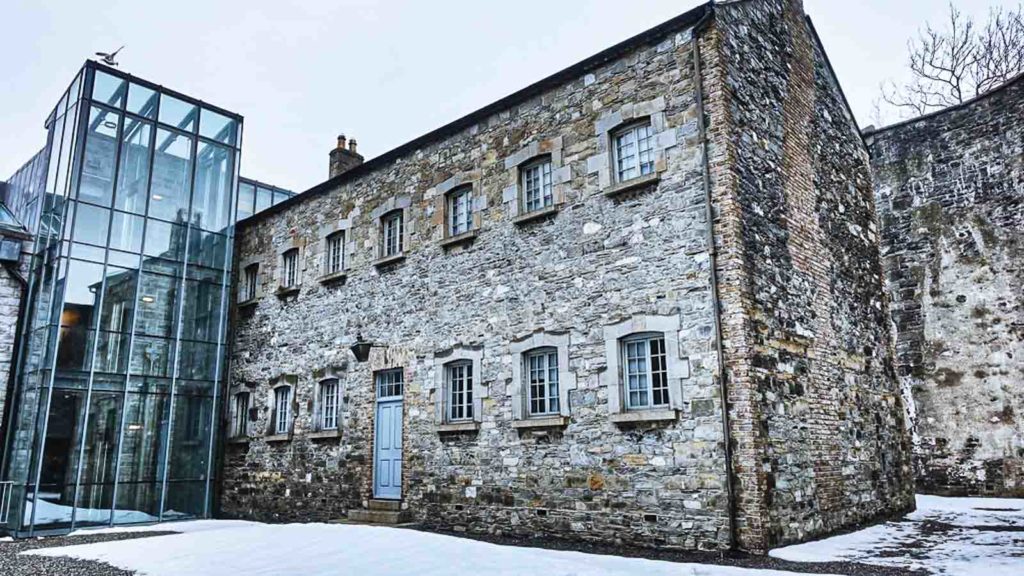

The architecture of Kilmainham Gaol reflects the 19th-century approach to confinement, shaped by ideas about punishment, discipline and reform. The building’s design aimed to impose order while restricting freedom, and its structure still communicates those intentions. Upon entering the gaol, visitors encounter long corridors lined with narrow cell doors, an arrangement intended to isolate inmates and limit contact. The high ceilings and exposed stone contribute to a sense of severity, reinforcing the psychological effect of imprisonment. These architectural choices were not accidental but part of a broader philosophy that viewed strict control as essential to rehabilitation.

The East Wing, constructed in the mid-19th century, embodies a belief in surveillance as a tool for maintaining discipline. Its radial layout, with cells arranged around a central viewing point, allowed officers to monitor multiple areas simultaneously. This design mirrored trends seen in other European prisons of the era, where visibility played a crucial role in enforcing order. The iron staircases and walkways were built to amplify sound, ensuring that any movement would be easily detected. Such features illustrate how architecture functioned as part of the institutional system, shaping behaviour as much as physical boundaries did.

Yet Kilmainham’s architecture reveals more than strict enforcement. Over time, overcrowding and practical demands forced the building to evolve. Additional spaces were repurposed or expanded to accommodate fluctuating inmate populations. These changes highlight the tension between ideal design and the realities of 19th-century justice. Reports from inspectors noted that the original intentions behind the architecture often clashed with conditions on the ground. The strain placed on the building offers insight into the social and economic pressures faced by communities at the time, as well as the limits of the penal philosophy that guided its construction.

Walking through the gaol today allows visitors to observe both the original structure and the layers added over decades of use. The combination creates a compelling narrative about the relationship between architecture and social policy. Kilmainham stands as a tangible reminder of how confinement was understood and implemented during a transformative period in Irish history. The preserved building helps guests reflect on how these ideas have changed and how the physical environment shaped the experience of imprisonment. Through its architecture, the gaol continues to communicate lessons about discipline, resilience and the evolving nature of justice.