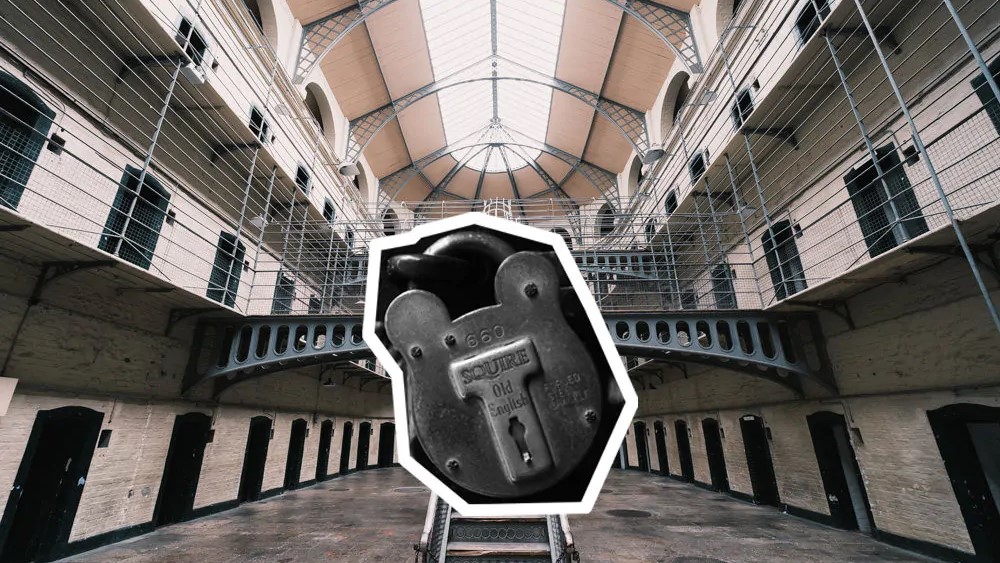

Kilmainham Gaol has served as the backdrop for several major film productions, a role that has added a modern layer to its historical identity. Long after the prison closed, directors began to recognise the building’s potential for storytelling. The gaol’s stark corridors, towering ironwork and atmospheric lighting offer a setting that would be difficult to recreate on a studio lot. Its authenticity brings a distinctive visual texture to films, allowing audiences to feel immersed in the scenes without relying on elaborate sets. Many visitors express surprise when they learn how frequently the building has appeared on screen.

One of the most recognised productions to use Kilmainham is the 1969 film “The Italian Job,” which included scenes shot inside the prison. The building’s imposing structure contributed to the film’s tone, illustrating how seamlessly Kilmainham can adapt to different cinematic genres. Over the years, other productions have followed, using the gaol to represent various historical periods and fictional locations. Its architecture offers flexibility, enabling filmmakers to convey a sense of confinement, tension or historical depth. These appearances have helped introduce the building to international audiences who may have been unfamiliar with its cultural significance.

Film crews working inside Kilmainham have often commented on the unique challenges of shooting in a preserved historical site. The need to protect original materials requires careful planning, as equipment must be positioned without causing damage. This sometimes leads to inventive solutions, with cinematographers finding ways to use natural light or existing structural features to create the desired effects. These limitations, rather than hindering creativity, often enhance the authenticity of the final scenes. Directors appreciate the opportunity to work in a space where history is visibly present in every frame.

Visitors who recognise Kilmainham from film scenes often find that the real building feels even more striking than its on-screen counterpart. Walking through the same corridors that appeared in well-known productions offers a different kind of engagement with the gaol’s character. It highlights how historical sites can evolve and continue contributing to cultural life long after their original purpose has ended. The building’s role in film production adds an unexpected dimension to its identity, blending entertainment with heritage and offering a reminder that history can reach new audiences in creative ways.